Reviews of Classic Movies: 'Mad Max'

There are few movie visuals that are quite as cinematic as a car on an open road. It’s something about the sense of motion, the inhabitants of the car looking out as they glide through a landscape, that mirrors our own experience of watching the film. And when a filmmaker can take that image and warp it – by setting the film in a post-apocalyptic wasteland, for example – it adds a whole new layer of symbolism, and a new level of engagement. This is one of the reasons the films in Mad Max series are accepted as classics. They take a simple story device (some fast-moving cars) and push the idea to its extreme, building characters and a world around it until the film moves past simple thrills and into something far more reflective, or perceptive.

Australian director George Miller – despite his claims he and his crew didn’t have a clue what they were doing when they made Mad Max in 1979 - must have had an inkling of what audiences wanted to see. Miller features high-powered action scenes, huge Outback landscapes, and some of the creepiest, most unpredictable villains put to screen. More importantly, he hints that something very wrong is happening in Max’s world as the story begins – nothing like the desolation to come in later films, but just enough to warn the audience that we're seeing what it looks like when civilization begins to falter.

Built on the foundation of that 1979 film, the latest entry in the Mad Max series hits theatres today, and for fans of the franchise, it’s been a long road. When I first heard about the new film, Mad Max: Fury Road, several years ago, I wondered what kinds of people would turn out to see it – how many would know the first three films, and how many would be stepping into George Miller’s world for the first time?

After all, it’s been 30 years since the previous film in the series (Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome), and 36 years since the original film. Compare that to other pop culture milestones, and it’s a lot of time for a film series to lie dormant, before getting a new sequel. It’s more than any gap between the films of the Star Wars series, the Indiana Jones series, or a handful of other long-running cinematic universes (to use the icky Hollywood buzzword). In cases like these, a delicate balance needs to be struck: reference enough of the classic material to make the new film feel like a true continuation of the story, while figuring out how to attract a whole new generation of viewers.

Sad to say, up until recently, I was among those who’d never seen the earlier films; so I decided to fix that before the new one came out. I wanted to know why the creators decided to revive the storyline, and pick up the action sometime after the events of the last installment. Knowing how remake-happy the industry tends to be, I was curious if there was something about the first film that made enough of a connection with people to avoid telling the story over from the beginning.

My hunch was right: anyone who goes back now to watch Mad Max for the first time, either to prep for Fury Road or to fill in the backstory, will be pleasantly surprised by how subtle George Miller and his team were. If your first taste of the Mad Max world is one of the Fury Road trailers, you’d expect the first film to look similar: a desert wasteland crawling with bandits wearing ghoulish makeup, who drive weaponized vehicles and battle over basic supplies like water and fuel.

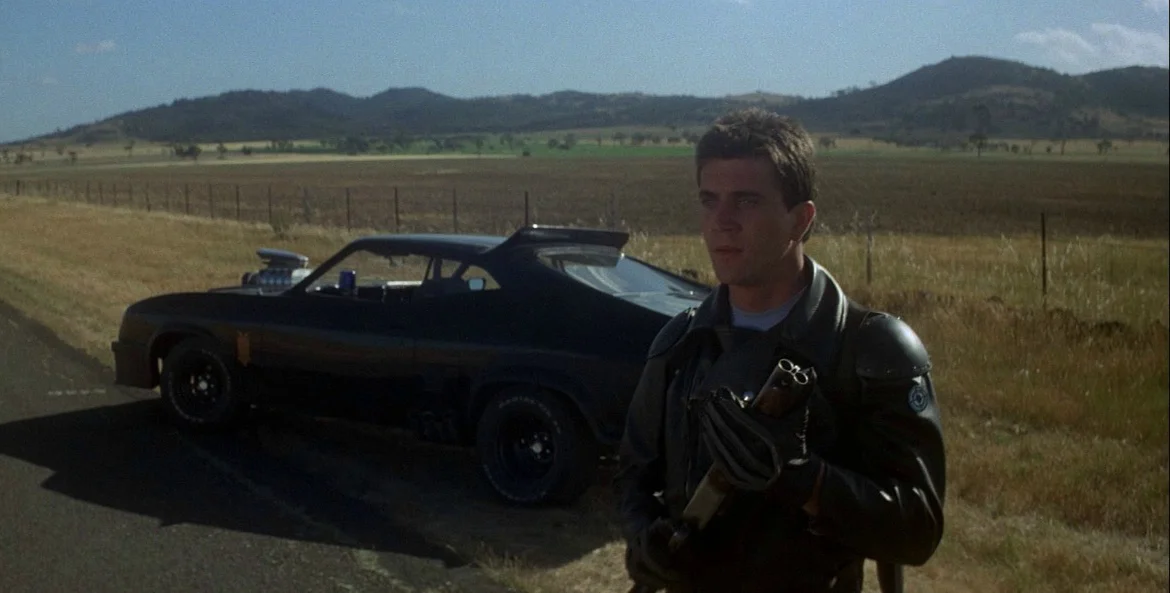

Instead, the first Mad Max shows us a world that’s just beginning to go to seed: Max (Mel Gibson) starts out as a fairly stable family man, who works as a patrolman for the near-future justice system that’s trying to keep the bandits in line. Were it not for the dilapidated buildings or the apparent absence of any other government, Mad Max would feel more like a cop drama than anything else. But with little offhand comments in the script, or specific visuals, Miller conveys a sense of how fleeting even this system will be. The coming insanity is pacing, just outside the frame, waiting to infect the minds of Max and everyone around him.

One of the fascinating things about Mad Max is how some of the subtlety feels like a happy accident at times – by not having a huge production budget, Miller and his team can only show certain details about the world. They don’t overwhelm us with huge, CG vistas or digital sets – the landscapes are brutally real, and actually communicate more by having less in them.

The film does show its age and technical inexperience at points; in the more glaring scenes, Miller occasionally under-cranks the camera to speed up some shots – a trick that’s almost as old as film itself, and isn’t that convincing any more. But the quirks sometimes help create a raw, unfiltered feeling that supports the film’s setting. Certain portions almost feel improvised (including the spectacular car chase near the beginning of the film), in a way that seems less and less possible now. One of Miller’s challenges with Fury Road was likely how much CGI to use – as filmmakers like George Lucas and Peter Jackson prove, CGI epics don’t always make good successors to earlier works on celluloid.

The other detail that might trip up viewers going back to the original Mad Max is its pacing, which drags in several long sections as Miller assembles the plot. For a while, it’s not entirely clear what kind of stakes Max or his allies are facing. His enemies (led by a bandit called Toecutter, played by Hugh Keays-Byrne) are so unhinged that we’re never sure what their goal is, and so it’s not until the final 20 minutes of the film that the characters really begin to face off.

As thin as the plot is in places, it’s easy to be drawn into the footage of cars and bikes racing forward, running each other down, each vehicle serving as an extension of the psyche of the character driving it. The swarm of motorcycles favoured by the bandits echoes their fractured impulses, and the powerful muscle car driven by Max is like a loaded gun: safe in the hands of a sane man, but dangerous when its user is pushed to the breaking point.

It’s all a logical precursor to the state of things when Fury Road kicks off, and it’s for that kind of serialized storytelling – decades before Marvel made cinematic universes cool – that allows George Miller’s debut to be more than a violent road movie or an exploitation flick. Mad Max gets two and a half stars out of four.

Have you seen the original Mad Max? Do you think it’s a good idea for the people seeing Fury Road to go back and watch the older films, or will the new film be better off kick-starting its own continuity? Join the discussion in the comments, and if you liked this review, share it with your friends and followers!