Power to the People: The Pros and Cons of Crowdfunding Movies

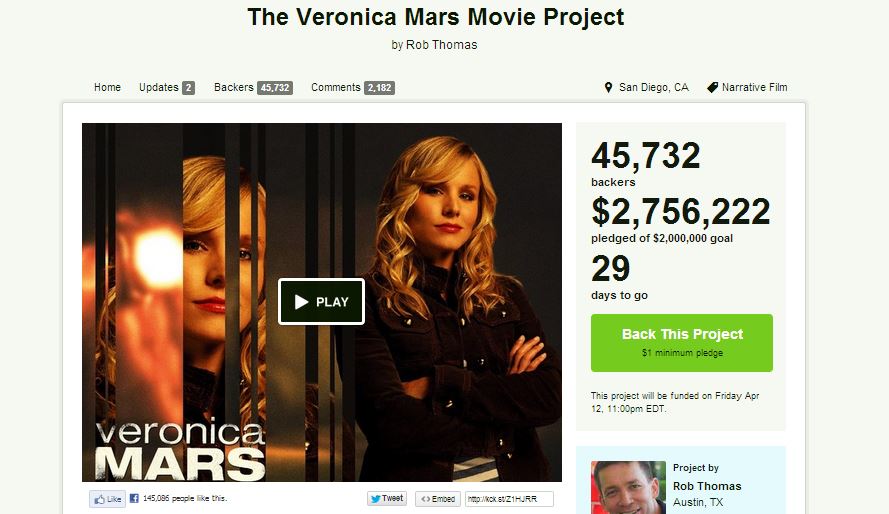

I’ll be the first to admit that I knew very little about Veronica Mars before its Kickstarter campaign launched yesterday. I had some vague memory of it being a career milestone for Kristen Bell, and that was it. But it’s fascinating how the TV show that ended in 2007 grabbed our attention with its pitch to crowd-fund a movie sequel on Kickstarter, setting a fairly lofty goal of $2 million. Fans rallied around the idea, and the campaign hit its goal in less than a day – as of this writing, it’s chugging towards $2.8 million in funding.

Maybe Veronica Mars is an outlier among movie Kickstarter campaigns, and it just happened to have a large, devoted fan base that was ready and willing to help revive the show as a movie. But the rabid success of the Kickstarter campaign speaks to the larger trend of crowdfunding movies, highlighting some interesting pros and cons with the strategy. After all, the Veronica Mars funders now have a vested interest in the film, and if the finished product disappoints, I wouldn’t want to be on the receiving end of the Internet hate.

Of course, crowdfunding ventures like Kickstarter and Indiegogo - founded in 2009 and 2008, respectively – weren’t expressly designed to finance movies. They operate on a far more general scale, offering a fundraising platform for all sorts of projects – theatrical productions, video games, businesses, and charities. But crowdfunding is especially useful for movies because it trades on one of the things all fans want: participation in the project.

The real product being sold isn’t the long-awaited movie in question, but a feeling of being connected to the property, something that can’t really be achieved by buying a ticket or downloading a copy. It replicates the feeling of lending a friend some money – only in this case, you feel like the friend is Kristen Bell or Jason Dohring, or series creator Rob Thomas.

Sure, crowdfunding platforms also offer built-in rewards (like tickets to the premiere or set visits) at each level of donation, but I’d argue that for die-hard fans, the experience of helping a beloved series come back to life is enough of a gift.

From that perspective, it’s unsurprising that the Veronica Mars Kickstarter took off so quickly. And when you consider the position of the people behind crowdfunded movies, it seems like a great opportunity.

After all, getting together $2 million can be tricky in the film industry. You have to convince studios and other financiers that your project will be profitable, and claiming that you already have a huge fan following isn’t always enough. By throwing out a funding challenge directly to the people who want the project to happen, filmmakers can avoid the negotiations and creative control that usually comes with company funding.

It’s important to remember the downsides to crowdfunding, though. Namely, all the thousands of backers in a crowdfunded movie suddenly become amateur movie producers, meaning they get to feel even worse when a project fails to impress. That’s not to say that the Veronica Mars project is doomed to let down its fans, just that the element of doubt still exists.

The Kickstarter backers won’t feel the $200 million punch to the gut that a studio does with a project like John Carter. But if a crowdfunded movie is a dud, the fans will feel cheated – to bring back that "loan to a friend" idea, it would be like the friend wasted the cash on a fancy car, instead of investing it in a business idea. With crowdfunded movies, the viewers have a much bigger stake in its success.

With the Veronica Mars Kickstarter, fans are no longer passively watching a new installment of their beloved story – they are active parts of the production. If the movie takes its characters in the wrong direction, fans can’t argue that the creators were at the mercy of business decisions by producers – the fans are the producers, and they are partially responsible for the creators’ mistakes.

This is connected to the other danger of crowdfunding movies – creative impunity. If I were a filmmaker launching movie Kickstarter, a part of me would be saying, “Well, now I don’t have to answer to a big company if this thing falls apart. I can do what I want with the story, because the fans are already behind me!”

Again, this may not be Rob Thomas’ motivation in the case of the Veronica Mars movie, but it must be tempting. The success of a movie Kickstarter must hold a certain validation for filmmakers – financial proof that what you’re pitching is a good idea – even when the success of the film is no more guaranteed than if the money came from a studio.

I probably won’t be first in line to see the Veronica Mars movie when it’s released, but it’s a topic I’m going to be watching closely. If the project succeeds, it will serve as further proof of the advantages of crowdfunding for underdog productions. But if it fails, I hope its backers appreciate that what really matters with movies isn’t whether or not you get to see another one – it’s the story that counts.

-

What do you think of the movie crowdfunding trend? Can it rival the traditional financing model for the movie industry, or will it stick to the realm of short films and independent productions? Post your thoughts in the comments section, and if you liked this article, share it with your friends and followers! You can also browse through my other posts about the movie industry here:

-

HFR 3D is Revolutionary, Frustrating and Weird | How Disney’s Money Will Save Star Wars

The Pros and Cons of Making The Hobbit into a Trilogy

-